Mirrored

They certainly went in for reading from either end

Back in Heather and I visited the British Museum. That outing was to see an exhibition on some ancient history, The World Of Stonehenge. we returned for some different ancient history, though one that arguably has more influence on us today, as we visited Hieroglyphics: Unlocking Ancient Egypt.

We arrived nice and early, where it turned out Heather hobbling around with a stick has some benefits, as we skipped any sort of line and were slipped through the barriers and straight into the grand old museum. There was plenty of time for a sit down and some coffee beneath the grand roof of the great court before heading back in time to the period of pharaohs and grand monuments.

The Key

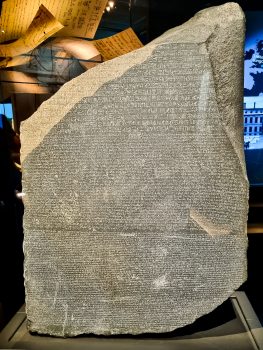

The Rosetta Stone allowed the decryption of hieroglyphs due to also being in Coptic and Greek

More accurately the thrust of the exhibition was a few thousand years later, and the reason we know so much about the history and culture of ancient Egypt. The story is of course fairly familiar to anyone with an interest in the Egypt of the deep past, beginning with Napoleon Bonaparte and his campaign in Egypt. In an unusual move the expedition through Egypt included a scientific delegation with the French army. It was they who found one of the most famous objects of this period of history (and incidently, an early star of this exhibition), the Rosetta Stone. Following Napoleon’s defeat the stone made its way to the British Museum, where it remains on (normally open) display. The importance of the stone, actually one of countless “steles” of the period, was almost immediately realised, for it contained a text not only in readable Greek, but also two undeciphered at the time scripts—the familiar Hieroglyphics and, partial key to understanding, Demotic in the centre.

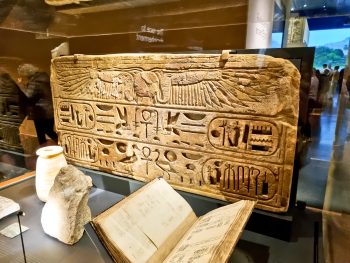

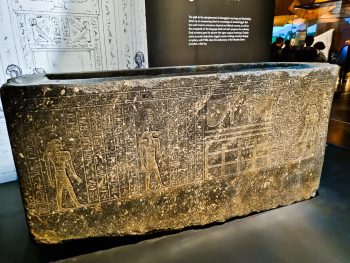

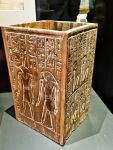

The Magic Coffin

Thought to hold mystical powers due to the hieroglyphs it’s adorned with

The first part of the exhibition set the scene for the translation efforts sparked via the Stone’s discovery. While it touched on the mystery and magical mystique with which hieroglyphics had become endowed, one thing which seemed lacking was any word on just how the meaning of the symbols was forgot. This actually seems astonishing given they were still in use, at least as sacred writing, when the land of Egypt was interacting with ancient Greece and Rome. There are a number of cultural and political reasons perhaps for the lapse but it always seems slightly astonishing that none of the knowledge obsessed Greek’s fully discovered and recorded the correct usage.

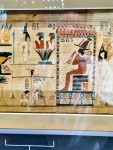

Symbols

All representing language, in three different ways, on the Rosetta Stone

Putting that aside, the exhibition did a decent job of introducing hieroglyphics, and the mystery which surrounded them (and hence, ancient Egypt) at the beginning of the nineteenth century. That all led nicely up to the Rosetta Stone, sitting majestically alone. Heather was, as always, quite mesmerised by it. And it was a wonderful opportunity to actually get up close and personally with, at times, zero other people around it. A chance to study the scripts without peering over the heads of crowds of people. It draws you—three scripts, two so familiar, and it’s almost as if one could only stand looking long enough understanding would arrive.

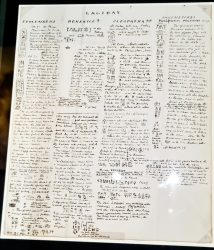

Barely Readable

And that’s just Young’s scrawled handwriting

No surprise then that the Stone’s discovery initiated something of a scramble to work out how to get from the Greek to Hieroglyphs. It is this the second part of the exhibition dealt with, via the “race” between two of the main protagonists and contributors. On the one hand sat the Englishman Thomas Young, sometimes described as “the last man who knew everything”. Young was a polymath of the highest order, who made major contributions to a baffling large number of fields. As a physicists he is something of an idol. Anyone who has sat through secondary school science lessons has probably dangled weights from springs and learnt about Young’s modulus, while his double slit experiment remains one of the most fundamental observations to this day. Jean-François Champollion meanwhile was a simply brilliant linguist, speaker of numerous languages (modern and ancient). Though he was often less than generous in acknowledging the contributions of others (including Young), it was he would eventually decipher the pictograms of ancient Egypt—having arrived at a major breakthrough he famously ran to his brother, declaring “I’ve got it!” before collapsing in a slightly alarming Eureka moment.

The problem with this part of the exhibition was it mainly consisted of a number of notebooks and papers, written in several languages none of which I read (and even Young’s English scrawl was difficult to parse). It was all about, here’s so undecipherable scribble about some other scribble which at least consists of pretty pictures. It’s interesting primary material for the efforts to understand hieroglyphs but doesn’t make for that compelling viewing.

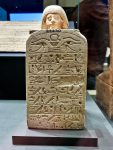

Wall Of Kings

Each part denotes the name of a ruler

Fortunately things quickly picked up again. Understanding hieroglyphs allowed all those Egyptian inscriptions to be read, and opened up and entire world and culture. It overturned a lot of what was believed but also gave deep insight into the lives and surroundings of those living then; their beliefs, their hopes, their everyday lives. As well as huge lists of pharaohs and big stenes containing declarations were more everyday items—statues, and measurement tools, and boundary markers. And even a little collection of relatives of the Rosetta Stone, versions found after the original key to decipherment. A great long Book of the Dead lined one wall, spells for the afterlife now understood. Elsewhere history rewritten, the everlasting stone mutilated as a name is erased from the record. And perhaps my favourite piece of information—the ancient Egyptian word for cat was “mioew”.

In all then a fascinating exhibition, dropping off slightly into too academic a focus in the middle, but still well worth visiting. By the time we emerged it was lunchtime—the British Museum’s easier to find options being a lot less pretentious than those up on Exhibition Road in museum land. That left us an afternoon to explore, determined to avoid the usual suspects and wander our less beaten path around the galleries.

Opal Jug

Almost glowing in its translucence

We fairly much succeeded, once again marvelling at the seeming organised chaos that is the Enlightenment room before finding our way to the collection which is the Waddesdon Bequest. There we were greatly impressed by a number of drinking vessels and jugs, some of which seemed to shimmer magically in the dim light of the room, as well as the intricate delicacy of prayer nuts—which once again made me wonder at all the wasted skill and ability, and effort, of man in the name of some silly religion.

The Unmovable One

Now he looks mean

We nearly got distracted by old loves passing through Mesopotamia, the Standard of Ur and the Royal Game of Ur drawing us for a look before we caught ourselves. We also forced ourselves to walk through (more) Egyptian before finding something new to look at. At the top of the museum we found Japan and a fascinating look into the eastern culture. With a pantheon of gods and goddesses to rival any Greek or Roman there were certainly plenty of statues of ferocious looking deities, well matched with the samurai armour on display, but also a number of calmer, soothing creatures who’s very posture and look seemed to speak of peace. Perhaps that is something that speaks to the collection of serene ceramics and art collected in one of the rooms.

That was about all we had the energy for. There was the inevitable tour of the shop, and then a stroll out and managing to find a table in Museum Tavern opposite by sheer luck to rest ourselves before heading home.

Fist Bump

Hieroglyphs

The Magic Coffin

The Key

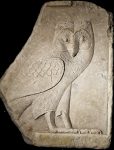

Owl

Symbols

Rosetta Relative

Working Out

Barely Readable

Hieroglyphs

Mirrored

Name Indicators

Wall Of Kings

Nice Box

Towering

Dude

Ancient Alphabet

Mioew!

Cut Away

Coptic Jars

Weighing

Ruler

Boundary Stone

Woman With Duck

Biggus Dickus

Interesting Bowl

The Knuckles Player

Red Jug

Opal Jug

Begging?

Silly Face

The Unmovable One

Angry

Spikey

Serene

Squat

Comments and Pings